contact us: gse-csail@gse.upenn.edu

The Elusive Goldilocks Model of School Reform

I wrote the other day about the problem with making too much out of the paper promises in state ESSA plans. After all, what really matters is how assessments, accountability systems, interventions, and the rest will actually work—and there's often no way to really know this until rubber meets road. Of course, waiting for and then watching that rubber-meets-road stuff is tedious, frustrating, and frequently yields a mixed bag of conclusions—which helps explain why it gets short shrift.

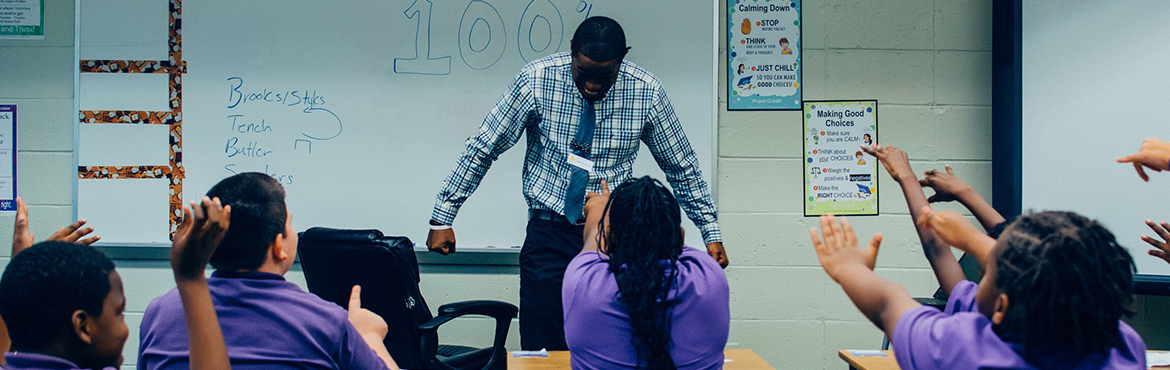

That's why it's worth delving into that side of things whenever possible. On that count, Adam Edgerton, a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania's Graduate School of Education, recently shared with me a thoughtful take on practical challenges states confront when it comes to accountability. In particular, he flags the challenge of striking a Goldilocks balance of being more "supportive" without simply being squishy. I think his musings offer a nice window into what's really happening on the ground in some states, and thought them worth sharing. Here's what he had to say:

As states explore new approaches to school accountability, U. Penn's Center on Standards, Alignment, Instruction, and Learning (C-SAIL) has interviewed dozens of state officials and found a popular new mantra in state departments of education: Accountability should now be "supportive, not punitive." Supportive states provide extra resources to struggling schools with fewer strings attached. For example, a state may send coaches to struggling districts and invest in technology infrastructure rather than mandate specific professional development activities or require new leadership. On paper, this approach sounds great to many tired of the No Child Left Behind-era high-stakes model. But few have thought through all the complexities or the perverse incentives this "supportive" environment could create.

Our C-SAIL team has examined accountability systems in five very different states: California, Texas, Kentucky, Ohio, and Massachusetts. These states represent two extremes when it comes to accountability. At one extreme, California has no summative scores for schools at all. It is specifically designed not to rank and compare schools using these scores and avoids prescribing solutions. One reason for this is that it seeks to eschew the types of gaming-the-system behaviors that NCLB created. Said one California official, "I tell people all the time that the old system was like playing tic-tac-toe. The new system is like playing chess. Right now our school sites don't know how to play chess yet, and the message that we're getting from the state, which I think is the appropriate message, is that this shouldn't be a punitive process."

In other words, it's much harder to game the new system when raw test scores have less weight.

At the other extreme, Ohio is doubling down on NCLB-style accountability and requiring 80% of all students to be proficient in reading and math by 2030. The state uses an A-F achievement ranking and can appoint CEOs to run failing schools, convert them into charters, and modify teachers' union contracts.

As with most education policies, the results of these accountability measures and their associated takeovers are mixed. But when I look back at where I taught—a Massachusetts high school that once graduated fewer than half of its students—it now has both graduation and proficiency rates over 70% since state takeover began. I still believe philosophically in the importance of local control, but there remain school districts throughout the country that seem to benefit from this type of outside pressure.

Sometimes takeover works, and sometimes it doesn't. It often comes down to a complex mix of personalities and politics. Without accountability's shock to the policy system, stagnation may take hold. We see this now in California's current lack of growth in student achievement—the entire state has stalled.

An all-carrots, no-sticks approach may lead to a new set of unintended consequences. Improving could theoretically mean a loss of resources. For example, imagine that a school receives extra funding for automated phone calls, home visits, and community outreach to address chronic absenteeism. If its attendance improves past a certain threshold, the state may decide it no longer needs money for these programs.

It would be wrong to suggest that school leaders would perform worse to retain resources. But over time, we all find ingenious ways to manipulate well-intentioned systems—whether it's the tax code or the Every Student Succeeds Act. And it's far more likely that schools will simply not improve without external pressure. In C-SAIL's interviews with California state officials, these concerns are not merely hypothetical. They are a real challenge as states try to implement better systems of accountability without creating another set of unintended consequences—or repeating the same mistakes.

For me, what comes through most clearly is the simple point that no one knows the "right" way to structure school accountability systems. A few years back, the concern was that the NCLB system was too punitive. Now, there's a concern that some of these systems will be too soft. And that's okay. After all, no one has the "right" way to hold hospitals or airlines accountable, either.

Accountability is part judgment, part measurement, part values, and part experience. Good accountability systems evolve, grow, and allow for learning. What I find striking is how rarely this gets acknowledged, and how much discussion around accountability gives the impression that the participants think they've stumbled onto the one best model. Fortunately, unlike under No Child Let Behind, none of these participants are empowered to write these energetic hunches into federal law. But I'd be more heartened if the enthusiastic counsel gave more of a sense that it had been informed by a little humility along the way.

© COPYRIGHT 2025

© COPYRIGHT 2025